I DIDN’T marry my husband for his money, I swear. I married him because he is brilliant, funny, compassionate and handsome. He is also unlike any man I had ever dated. You see, he has a job.

A man with a job wasn’t a situation I had much experience with. I was raised by a mostly single mother; my father, who lived with us intermittently, could not pay child support. We lived on welfare, food stamps and the charity of relatives. Our telephone connection was a fair-weather friend.

I went into the world with ingrained ideas about money and spending: Never buy for full price what you can find on sale. Clip coupons. Outlets are preferable to retail stores, and garage sales trump both.

My boyfriends reflected my own financial and mental states. My first, an artist, was brilliant but unmotivated. He would spend his evenings drawing rather than doing his homework, blasé about his cascading grades. My college boyfriends filled the mold that he had cast: quirkily intelligent, witty and fun, but with no goals, only dreams, and no plans to realize them.

After graduation I found a day job that paid my rent and left my evenings free. My boyfriend at the time suffered from a paralysis of the résumé. I begged him to record a demo tape of his piano playing, but he feared losing control of his music. He picked fights and dumped me because we fought too much.

Then came my most heartbreaking boyfriend, who was born with a severe immunodeficiency. He actually did have a job but worked less and less as his condition worsened. His goals were quite different from those of my other boyfriends: he wanted to live to the age of 35. I watched him die at 26. My own life dwindled to denial and anger — I’m still working on acceptance.

A few bad career decisions later, I soon joined the working poor, living from paycheck to paycheck. With each witless temp job, I began to feel more and more like Edith Wharton’s fallen heroine Lily Bart, but without the drugs.

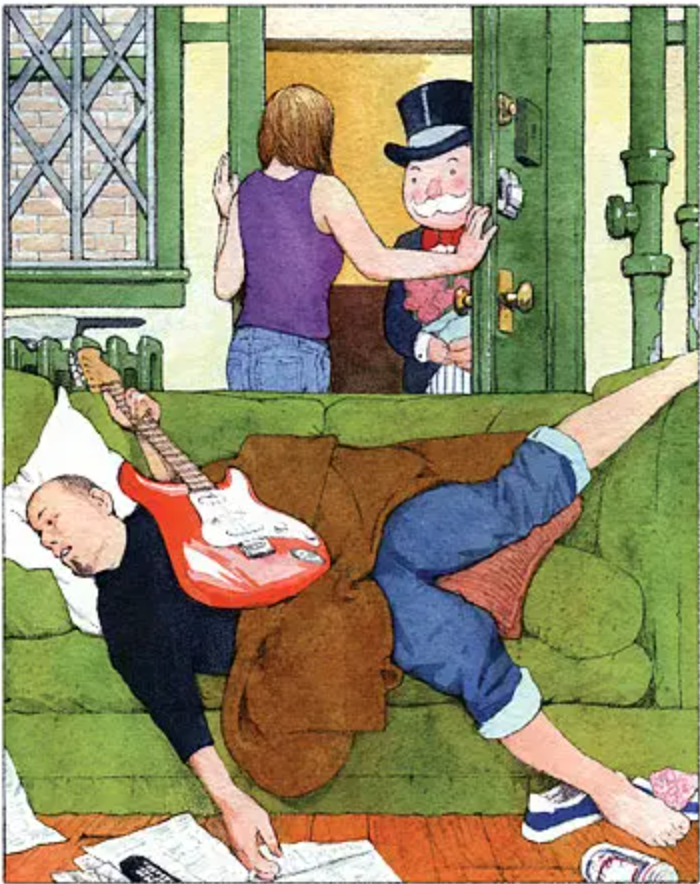

My outlook on money, as well as men, changed when my landlord tried to evict me, and I learned that the cost of keeping my rent-stabilized apartment would be a very expensive lawsuit.

With a bachelor’s degree in film and absolutely no direction, I had little idea how to earn real money without resorting to stripping or prostitution. So I took on a long-term temp assignment, which paid $15 an hour, more than I had ever earned. But after rent and legal fees, I had only $100 a week for everything else, which I allotted as $10 a day, $20 on weekends.

Each day was an exercise in how far I could stretch a block of tofu and a bag of rice with tomato sauce. At night, I would count any coins left over from the day and wonder if I could afford a new book, or a day off, ever.

I began volunteering part time at a start-up magazine, hoping for some of that mad Internet cash to trickle my way. It never did, but the work bulked up my flimsy résumé. I didn’t realize how even this minor evidence of ambition would create a gulf between me and my boyfriend at the time.

He always talked about becoming a naturopathic physician or even a vegan chef, but he never did any of those things. I worked two jobs every day and never got ahead. He lived rudderlessly, without ambition. After two years, ambition was all I had, the hope of a better life. Our difference was merely philosophical, but it cooled my ardor.

I began to form new ideas of the perfect man. He would not only have all the qualities that I required in a boyfriend, such as talent, intelligence and humor, but he would also have the one characteristic that my previous boyfriends lacked: a drive to succeed.

At 29, newly unattached and ready to restart my life fresh, I landed my first well-paying job as an editor, and for the first time I felt the constrictions of poverty slacken. The fact that I was also happy with my job led me to realize that I wanted a man who felt the same way.

I met Peter on an Internet dating service. He was easy to find. His profile mentioned my favorite authors and the stack of to-read books teetering in the corner of his apartment. He had also written these key words: “I like my job, and if I didn’t like it, I wouldn’t be doing it.”

We exchanged e-mail messages obsessively and talked for hours. We had the same likes (brown sugar in English tea, the novels of Barry Hughart) and dislikes (pimentos in olives, big-budget Jerry Bruckheimer movies). I thought we had everything in common. But when we met, I realized our one true difference: Although we both had ambition, he had already succeeded.

HE bought books and music on a whim. His clothes came new off the rack. He bought dinner for me in restaurants that required reservations, and he would order a side, an entree and a dessert in the same meal, while I ordered a simple salad with water. I would sit on my hands to keep from grabbing the good brown sugar from the sugar bowl. In the beginning, I thought it was best to hide my financial insecurities from him.

Within months, Peter made me feel like his best friend and partner in life. He was stable yet go-getting, practical yet adventurous (without the concomitant adrenaline addiction). He didn’t call me every night with a new tale of work-related woe; he talked about his productive and interesting day. In short, he was an adult.

To assuage the guilt that gripped me whenever he picked up the check at restaurants, I cooked for him, or I would take him to brunch. But even with my relatively well-paying job, frequent brunches for two put more stress on my bank account than it could tolerate.

Finally I sat him down and told him the truth: I could no longer afford him.

He countered that money wasn’t a problem for him.

In the past, I had tried to take care of my boyfriends. I had hoped that my encouragement would motivate them to succeed where they had previously floundered. It never happened, at least not while I was dating them.

I did not, could not, imagine that a boyfriend would take care of me. Until Peter. And this was an undeniable element of my love for him, that he was coming to my rescue. I’d never had a hero before.

One night over yet another dinner that he paid for, I confessed my fear that if I were to lose my lawsuit over my apartment I would become homeless and have to move to New Jersey. Or Indiana.

His response almost made me do a spit-take: he offered to buy an apartment for me.

He must really love me, I thought, or he wouldn’t make the offer, right? Or is this something men do for women? Would he suddenly grow a mustache and then twirl it menacingly while quoting the amount of interest I owed him?

His generosity brought me to where I finally asked him about his money. How rich was he, really?

It turns out he wasn’t — by New York City standards. But he earned more than I ever could hope to. And he had never been poor. Even during college he had well-paying summer jobs, so when his friends were eating ramen, he was eating ramen with steak.

In my childhood, the best day of the month was when our food stamps arrived. One month my mother bought a special treat for me: red-hot cinnamon candies. I reached for them, but in my excitement, I dropped the container. The little red hearts skittered across the linoleum, dancing away from me, disappearing under the stove. It all slips away.

That was the worst thing about being raised in poverty, never being sure if the objects of your love — candies, apartments, fathers — would be there from one day to the next. Candies can disappear. They weren’t really yours to begin with.

IN the end, although I was tempted by Peter’s offer, I knew I couldn’t pay the maintenance, the mortgage and his loan simultaneously, so I turned him down. Later he offered to give me a credit card in my own name that would be linked to his account, in case of emergencies. But I couldn’t use it. Spend his money? What if he disappeared? But he said he trusted me, and I, in turn, had to trust that he wouldn’t leave.

He didn’t. A mere two days later, Peter proposed on bent knee. His offer left me, for the first time in my life, without a witty comeback. I was too stupefied to say anything.

Then he whisked me off to Paris. I have always believed I should pay my own way in the world. But “We’ll always have Paris” would not have been true had he not given it to me as a gift, and I’m glad I was able to accept it. Sometimes generosity is about accepting what is given. Sometimes “Thank you” is as much a surrender to faith as “I love you.”

We live in my minuscule apartment because real estate prices have skyrocketed in the time since Peter’s offer, in 1999, and we can’t afford to buy a place in Manhattan. But at the end of the month, we have money left over. When I’m in a rush, I take a cab, a once-unthinkable extravagance. For my birthday, Peter took me out to a Broadway show; our nondiscounted tickets cost more than $100 each.

Wanting a nice blouse for the occasion, I bypassed the nearby Barneys in favor of Filene’s Basement. I could have afforded any shirt in the store. But in the end I chose one that first had been marked down, then put on sale. Because some habits, alas, are more like scars.