Media tie-in novels (for the purpose of this article, I’m focusing on tie-in novels rather than novelizations, comic books, and games) add new dimensions to a familiar world, a world where the characters that fans admire continue their adventures beyond cancellation.

Media tie-in novels shed light on briefly skimmed minor events and answer such trivial-yet-burning questions as, “Will Phoebe find true love?” (Charmed: Sweet Talkin’ Demon), “How did Avon wind up on that prison ship with Blake?” (Blake’s Seven: Avon: A Terrible Aspect), and “What happens after the Kilrathi surrender?” (Wing Commander: False Colors). These are answers that I, and tens of thousands of others like me, want to know.

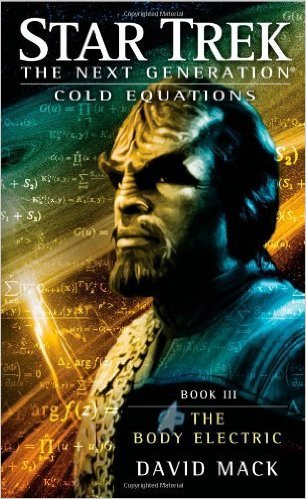

Like most novels, media tie-ins range in quality from shoddy to sublime, and media tie-ins are as diverse as the books you see on the speculative fiction shelves. Each author takes a different approach to similar material. If a person watches Star Trek because she likes Vulcan stoicism, there’s a book for her. If a person watches Star Trek because he likes Kirk’s take-charge attitude, there’s a book for him, too.

Karen Traviss, who writes Star Wars books as well as her own fiction (The World Before), says, “You have no idea how rich and varied [media tie-ins] are until you pick them up and read them. And there’s no single flavor…. The universe is shared, but the stories aren’t. Every writer brings their own distinctive style to the party.”

Professional authors with an arm’s length of publishing credits enjoy writing tie-ins, even when they can be writing in their own universes. Eric Nylund, author of upcoming Mortal Coils and two Halo books says, “The Halo books tap into a readership I always wanted to tap into, 14- and 15-years old, the Golden Age of science fiction, where the readers are very impressionable. That’s what really gets me jazzed — firing up their imaginations.”

Traviss says, “The sense of communal storytelling — both with other authors and the interactive process with the readers — is a very powerful experience.” Because she writes in the Star Wars universe, populated by other authors, it’s also a shared experience. “Other writers are lobbing stuff into the mix all the time, and you have to make that part of your storytelling too. It pushes your boundaries in unpredictable ways, which is terrific. It stimulates your imagination.”

However, not all genre authors feel the same way about media tie-in novels: The media tie-in industry exists to dish up more stories to satisfy the craving for a particular “property.” The original material is owned by a company. Therefore, the writers have no rights to their creation.

Norman Spinrad (Mexica), who has written tie-in novels for Star Trek and Land of the Lost, has more than one objection to the field. “The first reason is [the rights-holders] have endless requirements of the writers — what they can do and can’t do — and [the writers] get put through rewrites. It’s the same headaches as writing for TV, but for much less money. Another reason is the writer doesn’t own the property. The money isn’t that good, and the royalties are minimal. It’s dumb business.”

The writers of these novels work for hire, which could mean they receive a flat fee with no royalties, or perhaps a much smaller percentage than usual. Although many of the authors interviewed receive royalties, many others receive a flat fee only.

John Ordover, formerly an editor of the Star Trek line of books, says the arrangement is equitable. “[Tie-in authors] get two or three times the advance of a regular novel. Neophyte authors will be lucky to get $4,000-$6,000 for an original, but they’ll get $8,000-$12,000 for a tie-in.”

Sean Williams (The Crooked Letter), who is paid royalties for his Star Wars novels, says the terms of payment does not bother him. “Does a lawyer working for large firm expect partnership percentages just for employing a new defense? Of course not, so why should we?”

Williams adds, “I apply the talents I possess to the best of my abilities to give them the sort of work they’re looking for.” George R.R. Martin (A Feast for Crows), however, does not believe that tie-in novels contain the best writing an author can produce. “The writer is essentially a hired hand, doing a job for pay, and in my opinion that doesn’t get you your best work. It’s like if you’re building your own new house, you’ll put more time and care into it than if you’re building a house for other people.”

Quality is an issue with Martin, as with Spinrad, who agrees. “I’ve seen this ruin the writer’s style.” He describes writers who have lost their own voices after submerging themselves in the world of the tie-in property. So media tie-ins, an entertaining diversion for the reader, may not be the best deal for the writer, either financially or stylistically. Even more sinister, they may not be good for the speculative fiction genre as a whole.

Spinrad says, “This stuff is driving out real science fiction. If you walk into a book store, what do you see? The majority of the books are tie-ins. And because tie-ins are multimillion-dollar commercials, they’re going to sell better than free-standing novels. I imagine that the science fiction and fantasy tie-ins in any given year far outsell every [non-tie-in] novel combined.” (Because publishing companies like Del Rey and Bantam do not comment on their sales figures, I could not neither disprove nor substantiate his claims.)

David Moench, publicity manager at Del Rey says that sales figures, “depends on what the property is. The popularity of certain movies and games helps the sales of these books — that’s what drives it. The casual reader sees the movie and becomes interested in reading more about that specific universe.”

Elena Stokes, publicity director at Tor Books, says, “The [production company] of What Dreams May Come gave us trailers and art, and even though the movie wasn’t that successful, we shipped 585,000 copies the month before the movie came out. [Another property] did not receive as much advanced support, so we only shipped 54,000 copies of our tie-in and did not have a good sell-through.” Supplying advanced artwork and other visuals to the people who sell books to the bookstores can ratchet up the sales of the book. Science fiction media tie-ins typically have this in abundance. (It makes one wonder why such efforts are not put into every novel.)

The average science fiction/fantasy first novel (paperback) sells approximately 5,000-20,000* copies. The media tie-in figures are more than respectable: In fact, they’re enviable.

But then there’s the question of bookshelf space: specifically, science fiction bookshelf space.

Media tie-ins are not the sole domain of the speculative fiction genre. Sweet Valley High, Little House on the Prairie, and CSI have all been tied-in. However, tie-ins are a mainstay of speculative fiction, and bookstores are devoting an increasingly larger portion of bookshelf space to them. Why is this happening to science fiction and fantasy, but not other genres?

In a genre based on speculation, the interviewees can only speculate. Margaret Weis (Mistress of Dragons) says, “I think because readers become so involved in the world itself. With fantasy and science fiction, [the readers] are interested in the whole exotic alien world, which is so different than ours. In a romance [the readers] care about the characters more than the world.” In other words, fans become so smitten with a certain universe, they crave stories placed there.

Williams says tie-ins are popular in science fiction, as opposed to other genres, because, “There’s still a gap between the imagination and what appears on the screen.” A good tie-in novel can bridge that gap.

Traviss, Ordover, and Williams believe that media tie-in books are good for the genre: These books lure readers to the science fiction department and reel them in. Williams says that media tie-in books were his gateway to “real” science fiction. “The first SF novels I ever read were Doctor Who novelizations back in the 1970s. Reading them (and, later, Star Wars, Blake’s 7, Space: 1999, etc.) encouraged me to read ‘serious’ SF when I found a library that stocked it.”

Weis has a suggestion to drive readers toward real science fiction as well as alleviate the stress of the shrinking book shelf: “The bookshelves currently shelve the [tie-in] books separately from our [non-tie-in] books. If they shelved the tie-in books together, it would be a big help.”

Meanwhile, Traviss has noticed a boost in her own sales, thanks to her tie-in work. “Star Wars fans have picked up my own copyright titles and really made a difference to my career. They might not even have looked at that section of the store if they hadn’t known me as the Republic Commando woman. In fact, a lot of reader mail that I get tells me exactly that.”

However, Martin disagrees. “I don’t think you build a career writing in other people’s universes.” He explains. “At an autographing, I once sat next to a writer who had done a couple of well-received Star Trek novels, and she had also had a number of distinguished novels of her own…I observed that some of the people who came up had her own novels and some of the people had her Star Trek novels, but no one had both. She had two separate audiences.”

Nylund is not sure if the readers of his Halo books will pick up his other novels. “I have a feeling that the readerships don’t overlap that much. But I’m sure there’s a subsection of people who read science fiction novels and Halo novels.”

However, Nylund has developed a strategy to steer his Halo readers toward his other fiction: “I have another book coming out that I think will appeal to the readers of the Halo books, which is a good bridge from the science fiction action of Halo to the science fantasy universes I create. I just started my own website and blog, and I’ll probably podcast a short story. People can listen to that and judge for themselves.”

We all do — judge for ourselves, that is. Personally, I find media tie-ins easy to read because the shape of the universe has already been created, and the author fills in the color. I tend to read them when I feel the need for light reading. Of course, not everyone agrees, but not everyone has to. That’s why we have more than one book on the shelves.**

* Thanks to Jane Jewell, executive director of SFWA. Figures are for paperbacks, first print run.

** The author would like to announce that movie and comic book tie-in rights to this article are available through her agent.