Just how far are authors willing to go in order to research their fiction?

Many only walk as far as the kitchen, for a caffeinated drink to jolt the imagination. Others make their way to their favorite search engine.

But some authors pack their bags and book a flight to Antarctica.

It’s called “extreme research,” that is, research that goes beyond cracking a book or conducting expert interviews. It means getting your hands dirty and building up real-life, full-sensory knowledge that writers can then pass on to their audience.

Australian author Sean McMullen says he performs extreme research to write with authority, to create details not found in other books, and most importantly, to give himself an empathy with his characters.

The real importance of extreme research, however, is that authors often learn information that would never have presented itself in front of a keyboard. Anyone can read that Paris has a subway system called the Metro, but carefully worded tourist brochures leave out the fact that passengers open the doors and leap off before the cars come to a halt.

So what nausea-inducing, bone-wearying, or just plain unusual things have these authors done for the sake of their art?

Syne Mitchell, author of End in Fire, found herself surrounded by sharp weapons (and the men who know how to use them) when she attended a knife-making conference to research a book. Author and editor Cecilia Tan did some hands-on, or rather, stomach-on, research, to test a character’s tolerance for candy.

Some writers even take extreme research to the extremes. Author Kim Stanley Robinson famously spent five weeks in Antarctica on a National Science Foundation program, researching his “Mars” trilogy.

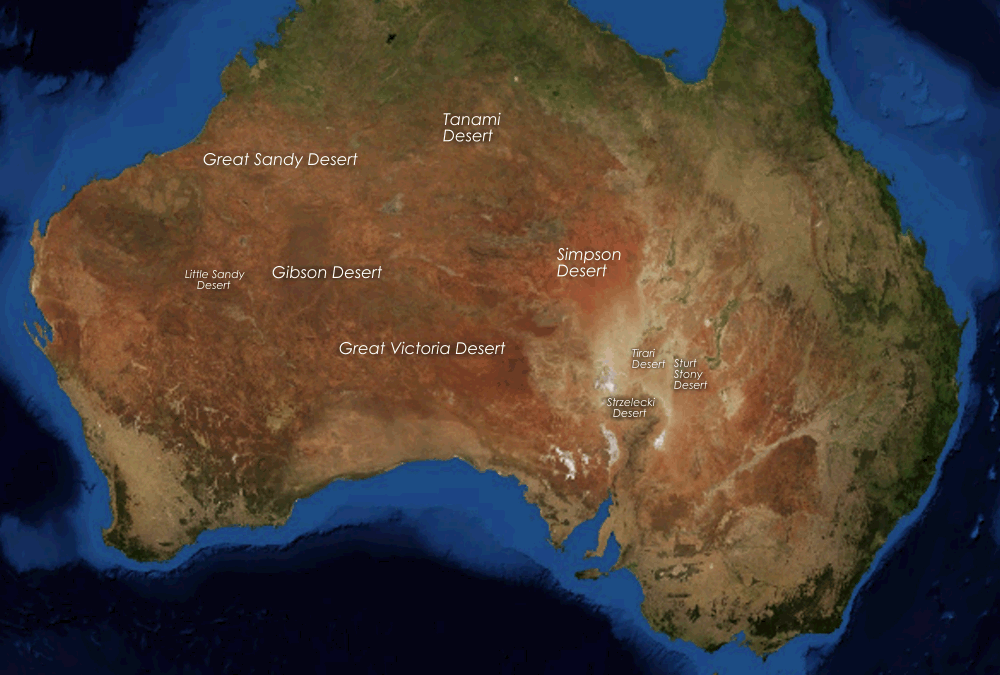

And McMullen walked the walk — in the Strezleki Desert — for his novel Glass Dragon when he spent a few days hauling 60 pounds of gear, shield, helm, battle axe, food and water, wearing chainmail and flat-soled boots.

Through extreme research, authors indeed learn about the topic they set out to study: Mitchell saw first-hand a variety of knives — art knives, utility knives, tactical knives — that she didn’t know existed; Robinson experienced the bitter cold of minus thirty below zero.

But most importantly, they learn things that surprise them.

For Mitchell, whose book is currently in progress, found the knife makers themselves were not what she had expected. “They’re a bunch of 50-something, grizzled, survivalist-looking people. During the break, we saw a mama chicken and ten fluffy chicks on the roof [of a building]. So the mama chicken flew down to the ground, and then a baby chick leapt — and plummeted. So me and twenty grizzled men covered our hands with ours mouths and screamed.

“They were as emotionally invested as I was about the baby chicks. These men then started engineering ways to make ramps for the chicks to come safely down, and all of the chicks got down alive. It’s not what I had expected.”

For her story “In Silver A,” Tan created a character who used sugar as a neurotransmitter. In order to learn how much sugar the character could reasonably ingest in one sitting, Tan said, “I ate a five-pound box of Swedish Fish. I learned that this was a reasonable amount of sugar for my character, and oddly, I was still hungry.”

McMullen discovered, “The discomforts, heat, etc were not as much of an issue as I had anticipated, oddly enough, and the chainmail was quite comfortable,” But he learned that the physical issues of such a trek were not as punishing as the emotional ones. “You feel highly vulnerable all the time; you are highly conscious of your feet and your water supply; you feel so very, very alone.”

However, such research, even in the name of good prose, has its drawbacks: it’s a time-consuming, potentially exhausting, and perhaps expensive (albeit deductible) way to learn.

Robinson, who learned firsthand that the mouth-puckering taste of ponds were fifty times saltier than the ocean, adds to that. “Some writers have ended up scared to write about anything they haven’t done themselves, and they end up cannibalizing their own experiences and trying too hard to have experiences they can then write about; I’m thinking maybe Hemingway, or Kerouac,” he said.

Mike Resnick, author of Dragon America, among others, believes, “Most ‘extreme’ research is actually something like Joe Haldeman getting blown apart in Vietnam, spending a year being put together, and years later using the experience in both 1968 and The Forever War.”

But most worlds science fiction and fantasy exist only within the author’s imagination, which makes location scouting impossible. And how does one interview a character who is half-human, half-demon, when the demon world refuses to comment?

According to Robinson, “The most important ingredient for a creative writer is imagination; for the novelist, the sympathetic imagination that allows you to try to inhabit various different kinds of characters. Then the hands-on research simply becomes life itself and the people around you, and so all of us are always doing it.”

Although extreme research is not strictly necessary, it can provide insights and a potentially fresh discovery of a location or subject. And for those authors who create their own universes, these flashes of unexpected realism can be the perfect hook on which to suspend the reader’s disbelief.